The Great 8

The Great 8 are the Great Barrier Reef’s living icons. The creatures we all want to see! Ranging from reptile to mammals, from little to large, the Great 8 wish list reflects the outstanding diversity of the Reef. Have you always wanted to swim with turtles, or see the magnificent humpback whales in their natural environment? Below is everything you need to know about one of the Great 8 and how to increase your chances of seeing them!

Sea Turtles

These ancient mariners are well adapted to life in our oceans. With the earliest fossils of marine turtles dating back to 120 million years ago, these fascinating creatures are on the must-see list for most reef visitors. In the modern-day, there are seven species of sea turtle, with six of those found on the Great Barrier Reef.

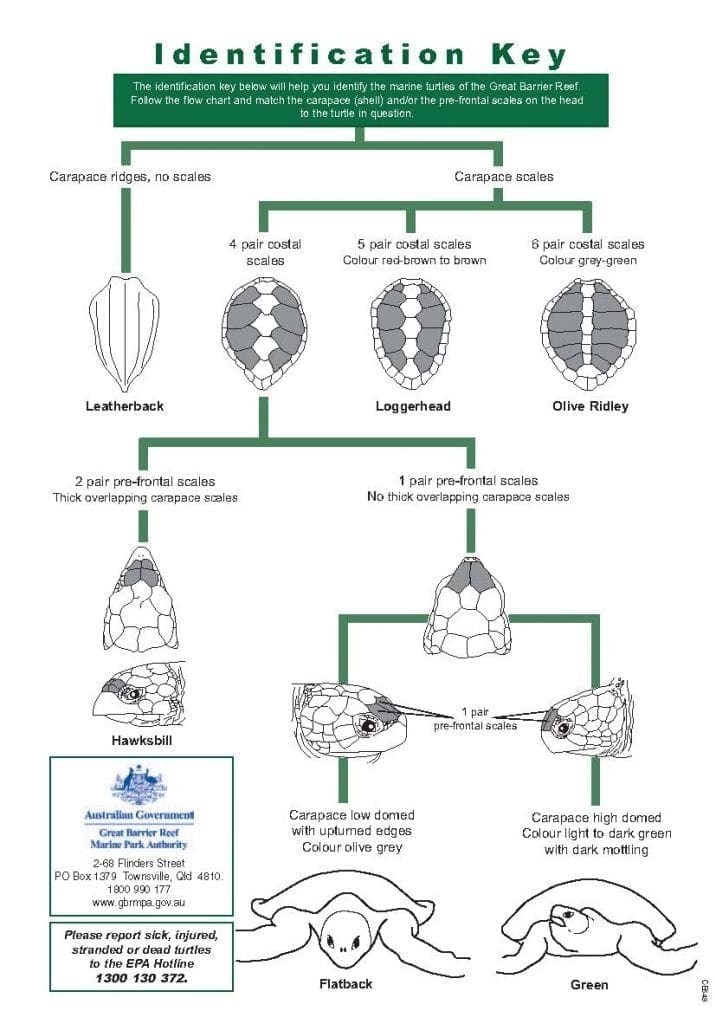

Although they all have slight differences in appearance, turtles are easily identified by its carapace (its shell) and paddle-like fins. The smallest is the Olive Ridley turtle measuring around 60-70cm, with the largest being the leatherback at up to 2.4m! The most common found on the GBR are the Green, Hawksbill and Loggerhead turtles with the Green turtles often providing epic guests experiences on both our Northern Exposure and Southern Lights tours.

Frequently Asked Question..

If six of the seven species are found on the Great Barrier Reef, which one isn’t?

The Kemp Ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys kempii), also called the Atlantic Ridley sea turtle is the only one of the seven not found on the GBR. As its second common name would suggest, the Kemp Ridley is generally found in the Atlantic Ocean, but there have also been sightings in the Gulf of Mexico. The Kemp Ridley is the rarest species of sea turtle and is classed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List.

The life of a turtle is impressive, their average life span is still unknown, but scientists believe that they can live to up to 100 years old! Between feeding, breeding and nesting, Turtles make incredibly long migrations during their lifespan.

Sea turtles mate between October and November and the females will always return to the same beach that they were born on to lay their eggs. When it is time to nest, the females crawl up onto the beach, digging a pit to lay between 50 and 150 eggs! The eggs take between 6 to 8 weeks to hatch and tend to hatch simultaneously around the full moon. The hatchlings have a rough introduction to life on Earth. Following the moonlight, they dash the ocean where they face numerous predators including, birds, crabs and sharks. Research shows that only 1% of hatchlings make it to adulthood, so protecting these iconic creatures is incredibly important.

Threats to Turtles

Turtles are no doubt one of the most iconic species of the Great Barrier Reef. For many, having the opportunity to swim a turtle is a once in a lifetime experience. These memories become holiday highlights for travellers during their time here in Australia. The Whitsundays is a real hot spot to see these beautiful animals. However, these iconic creatures are listed as threatened under Commonwealth and Queensland legislation.

Climate Change

As with most concerns on the reef, this ultimately starts with climate change. The rising air, water and sand temperatures are a cause for concern with turtle hatchlings. Did you know, the sand temperature in which the turtles incubate is responsible for the gender of the hatchlings? It is thought anything below about 28°c the clutch will be predominantly male, and anything over about 30°c producing mainly females, with optimum conditions sitting somewhere in the middle. With warming temperatures, scientists predict this imbalanced sex ratio is likely to cause population problems with not enough males to maintain a growing population.

Marine Debris

Turtles are mostly herbivorous, feeding on algae and seagrass however green turtles, in particular, are known to love to feed on jellyfish. It is thought the stinging cells of the jellyfish provide a narcotic effect, giving turtles the chilled-out persona made famous by Crush in Finding Nemo. However, plastic and marine debris are causing problems for marine life. Turtles have been known to mistake plastic bags for jellyfish and ingesting marine debris is thought to be one of the causes of the turtle’s population decline.

Check out some of Ocean Rafting’s initiatives to help reduce marine debris in our waters.

Artificial Light

Artificial light from urban areas is thought to be causing a decline in nesting success. Hatchlings use the moonlight to guide them to the ocean. However, scientists have noticed that hatchlings have been confused by city lights essentially getting lost on the beach.

However, with these threats, come solutions. Everyone can play their part to lower the carbon footprint or reduce their single-use plastics but if you would like some more guidance and information become a Citizen of the Great Barrier Reef here to learn how you can make a difference.

Turtles are no doubt one of our favourite encounters on the reef and we look forward to sharing our experiences with you on a tour in the future.